-- R.G. Menzies

-- R.G. Menzies

LIBERTARIAN/CONSERVATIVE DIGEST AND COMMENTARY FROM AN ACADEMIC PSYCHOLOGIST in Brisbane, Australia. My academic publications are widely read

Click on the title of any post to bring up the sidebar

Understanding national conservatism

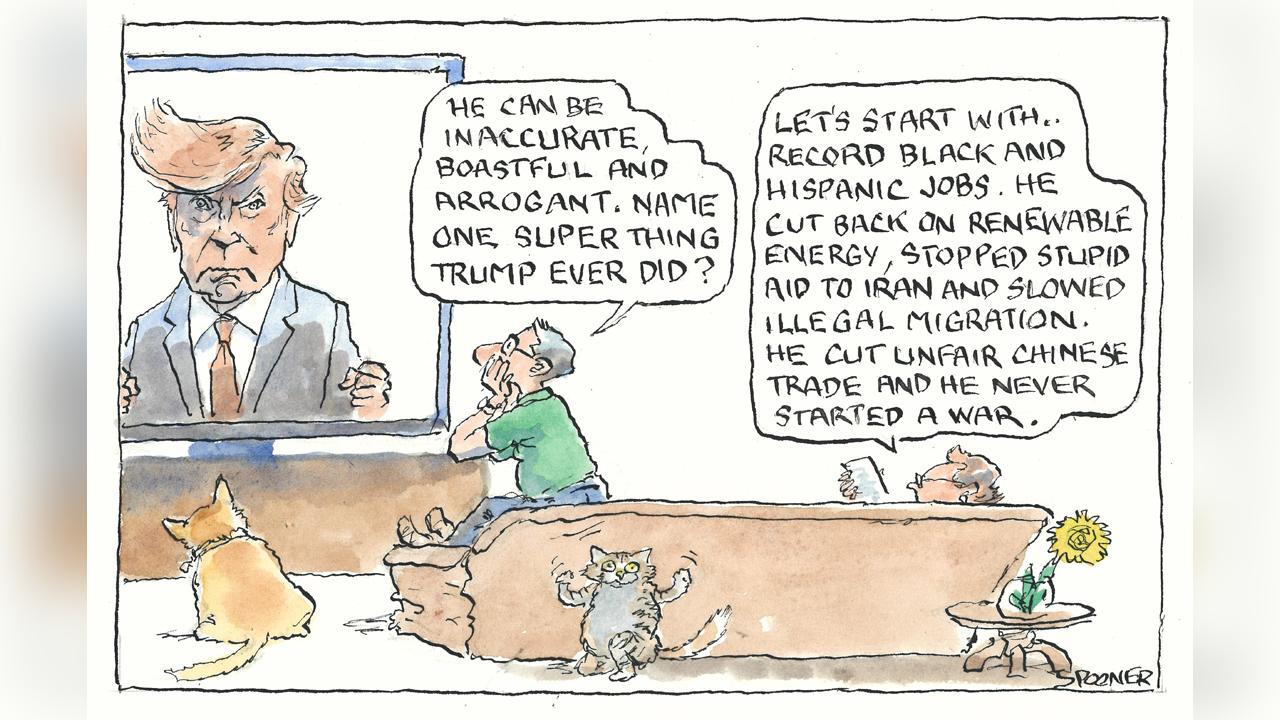

National conservatism sounds suspicuously like Trumpism, particularly on trade issues. "Free trade" has always sounded good to conservatives but Trump showed that it should not be an all-powerful consideration.

And Trump was not really being unorthoox in his trade restrictions. Economists have always recognized exceptions to the desirabiity of free trade: "Infant industry" and the "Australian" cases for instance. And the "supply-chain" difficulties presently besetting trade rather vindicate that

The Economist, the British magazine well-known for its particular metropolitan liberal worldview, had a pearl-clutching cover piece last week where it bemoaned ‘the growing peril of national conservatism’.

‘It’s dangerous and it’s spreading,’ the editorial warned its readers – making it sound like some new Covid variant.

What exactly is national conservatism?

Australians could be forgiven for being a little in the dark, for while there have been national conservative conferences in Washington DC and Florida in America, and in London, Brussels, and Rome in Europe, there has been nothing similar so far here. There are no mainstream Australian journalists who describe themselves using that label. Nor, unlike elsewhere, are there leading politicians or any groupings in any of our mainstream parties who march under that banner. I have found it a struggle to get those involved in the think tank world and in centre-right politics in Australia to even understand the concept properly.

The Economist labelled national conservatives as those ‘seized by declinism’, ‘the politics of grievance’, and those who see the ‘state as its saviour’. But that is unfair and does not do this intellectual movement justice. National conservatives have a deep philosophical critique of the assumptions held by policymakers in the capitals of the West. As some of the leading intellectuals of the movement, like Yoram Hazony, have explored in great depth, they are critical of aspects of classical liberalism and the dominant worldview which over-emphasises the sovereign individual, rather than the family, the nation, and our religious traditions as the source of our prosperity and freedoms. They believe the focus in centre-right circles has, in recent years, gone awry. In the words of Italian Prime Minister Georgia Meloni, it is time to ‘put conservatism back into its traditional sphere of national identity’.

Perhaps the most obvious areas where national conservatives differ from the current centre-right are in relation to immigration, trade, and foreign policy.

First and foremost, national conservatives reject the long-standing consensus on immigration. They believe that mass immigration perhaps poses more of an existential threat to the West than Soviet missiles ever did. Nations like Poland and Hungary recovered from years of communist domination. But it is far less clear whether parts of Western Europe and elsewhere will survive the ethnic conflicts and other threats to social cohesion that have been carelessly imported into their homelands. This is not simply about ‘stopping the boats’ or ‘building the wall’ – although many Western governments struggle to do even that. It is emphatically also about legal immigration. There needs to be a reassessment from first principles as to what level and what type of immigration, if any, makes sense for Western nations and our peoples going forward. In the Howard era, there was an oft-repeated line that because the government was able to control illegal immigration Australians welcomed higher levels of legal immigration. If that was ever actually true, it is not true now.

National conservatives also recognise that the trade and investment policies of the West need a serious rethink. They reject the idea that the end goal, beau ideal, should be open borders trade and investment between nations, without regard to their differing economic, social, or political circumstances. To be clear, this means large numbers of Australia’s existing trade and investment agreements, including but not limited to, the one we signed with China, will need to be torn up or at the very least significantly redesigned. Our trade and investment policies have created boom towns in places like Shenzhen and Bangalore and rust belts in places like Stockbridge, Elizabeth, and Youngstown. They have gutted our national industrial capacity and destroyed communities. They have turned us into exquisite connoisseurs of imported goods, rather than producers of anything other than primary produce or overpriced housing to sell to foreigners. The idea, so beloved by The Economist, that it should be as easy to import manufactured goods from China to Australia as it is to import the same from England to France needs to be consigned to the ash heap of history.

National conservatives also believe that our foreign policy needs to change. The reckless evangelicalism that has characterised Western military adventures for well over the last quarter century needs to stop. What is needed is a new prudence that is focused instead on our vital interests (narrowly defined) and which is far more selective about the conflicts we allow ourselves to be dragged into. Large numbers of our people are simply sick to the back teeth of endless and pointless wars in places like Somalia, Serbia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Libya and elsewhere. These are places that they do not really care that much about, but which they or their children have been expected to die for. These interventions always seem to follow a similar storyline: some bad guy is the ‘next Hitler’, a particular incident is the ‘new Munich’. Unless we get involved and offer unlimited economic or military support, we are Neville Chamberlain-like appeasers. Certain politicians then get to globe-trot around the globe pretending they are the next Winston Churchill. Inevitably what then follows, many years later, is a loss of blood, treasure, and national prestige, the destabilising of entire regions and a flood of refugees, and all manner of second-order unintended consequences. In nearly all cases these are not grand ideological struggles, but messy intractable ethnic disputes where there are no pure actors on either side.

There are other areas of policy where national conservatives have new and constructive things to say, including on social policy – where a reconstitution of family structures and traditional ways of life is going to be as important as the reconstruction of our national borders and identity. But if there is one theme that unites this movement, it is that they are anti-Utopian. The left was in the past the utopian ones, the ones who liked to ‘imagine there is no countries’. But since the great victory in the Cold War the centre-right has also become increasingly un-moored from reality. It has ignored the importance of the nation-state when it comes to trade, immigration and foreign policy and many other issues. All national conservatives are asking is that we get real again.

https://www.spectator.com.au/2024/03/understanding-national-conservatism/

***************************************************

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments containing Chinese characters will not be published as I do not understand them