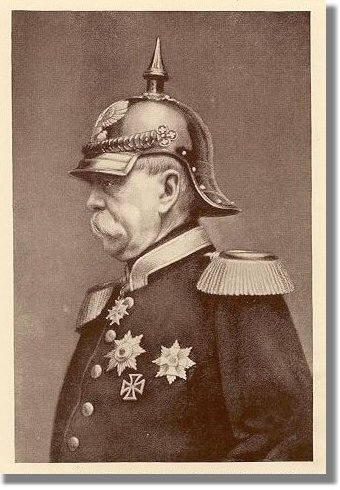

By contrast, the two greatest political figures of the late 19th century, Disraeli and Bismarck, achieved an enormous amount for humanity, peace and civility. Bismarck is normally pictured wearing his Prussian Pikelhaube (spiked helmet) -- though he was only in the reserves of the Prussian military in his glory years -- and that does tend to mislead people into thinking of him as a brutal militarist -- but that is the sort of ignorance you have to expect of people who have been fed the highly selective pap that passes for history lessons these days. In fact, Bismarck gave Europe a long era of peace and rapidly increasing prosperity.

After his great victory over Napoleon III at Sedan in 1870, one might have expected Bismarck to go on to a Bonapartesque quest to dominate all Europe, but he did nothing of the sort. The entire military campaign had not in fact been aimed at conquest at all. Bismarck simply used the war to unite Germany under the Prussian crown. So when the war was over, all but a small (but controversial) slice of formerly French territory was evacuated and Bismarck concentrated on creating the German empire -- not by force but by diplomacy -- albeit by diplomacy of a rather dubious sort at times. And a united Germany of course soon became the economic powerhouse that it has been ever since. But note this: from 1871 on, Europe had no major wars until 1914 -- a 43 year period of peace -- pretty unusual for Europe up until that time. And that long peace was largely Bismarck's doing. The united Germany's formidable military was a much a hindrance as a help because it made the rest of the world fearful and could well have encouraged a grand alliance against Germany. But by a series of ever-shifting and totally Byzantine series of diplomatic manoeuvres, alliances and treaties, Bismarck kept everybody off-balance and both Germany and the rest of Europe were left free to prosper peacefully and to develop the full fruits of the industrial revolution -- which they did mightily.

Bismarck was not as successful at heading off unrest at home, however. As in most of Europe, the newly-created industrial working class was in a fairly ongoing ferment -- a ferment in which Marx played a small part. So there were some serious rebellions, uprisings and disturbances. As in foreign affairs, however, Bismarck's ever-shifting policies and alliances managed to keep the peace overall. Regrettably, however, it was a fragile peace and violent socialism still lurked just beneath the surface. So after Bismarck was gone it broke out again -- as the powerful Communist and Nazi movements of the post-1918 period.

Bismarck's great English contemporary, Benjamin Disraeli, was far more successful at containing domestic unrest. Like Bismarck he saw the need for worker-welfare legislation as a means of buying social peace and both men were notable welfare innovators -- THE welfare innovators, it might be said. So what was the secret of Disraeli's success? Fundamentally, it was sentimentality. Although he was always vocal about his own Jewishness, Disraeli had a sort of love-affair with the English people that was only surpassed in more recent times by the love-affair that Ronald Reagan had with the American people. And the results Disraeli got were arguably as transformative as the results Reagan got. Disraeli had a great love and respect for English traditions and preached the virtues of Englishness incessantly. And he included in his embrace the ordinary English working people -- whom he saw as "angels in marble" -- people with great and good potential. He actually trusted the working-class -- an almost unheard-of idea among all the governing classes in Europe at that time. So he sponsored legislation that gave the workers the vote on a greatly increased scale. And they rewarded his trust by being far less susceptible to the political and social agitation that plagued their contemporaries in Europe. They developed a lasting trust in their national institutions that did far more for lasting peace and civility than anything else could have done.

At one of the great international political conferences of the time, Germany was represented by Bismarck and Britain by Disraeli. To Britain's considerable benefit, Disraeli ran rings around all of them -- causing Bismarck to make his famous admiring remark: "Der alte Jude. Das is der Mann" ("The old Jew. THAT is the man"). Coming from Bismarck, that was a compliment indeed. Disraeli himself attributed the greater social peace of 19th century England to Englishness but to a considerable extent it was in fact his own personal achievement.

Comments? Email John Ray

--

--

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments containing Chinese characters will not be published as I do not understand them